On Wednesday, October 16th, James Anaya, the UN Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, left Canada after a nine-day investigation into the conditions facing the country’s First Nations, Inuit and Métis populations. Anaya described the situation as a crisis. He referred to the gross levels of poverty and the deplorable living conditions in many First Nations communities, representing a blatant discrepancy with the overall wealth of the country as a whole. He expressed shock at the high levels of suicide, violence, ill health and addiction in Indigenous communities and called on the government to undertake a comprehensive nation-wide inquiry into the startling statistics of missing and murdered Aboriginal women across the country. He implored the government to take a less adversarial position towards First Nations and always seek consent and ongoing communication with these communities before occupying and further exploiting their land and resources.

Anaya released these statements on Tuesday and left the country on Wednesday. On Thursday, the RCMP was sent in to violently crush a peaceful protest being held by the Mi’kmaq people of the Elsibogtog First Nation against unlawful shale-gas exploration and fracking on their ancestral territory. Over 200 RCMP officers, some dressed in riot gear and armed with assault rifles and accompanied by snipers in camouflage, were sent in to break up the blockade.

On the same day that the violence erupted in Rexton, NB, the exhibition Beat Nation: Art, Hip Hop and Aboriginal Culture opened at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal. In fact, simultaneous to the pepper spraying, shooting with rubber bullets and mass arrests of First Nations protestors (along with Acadian and Anglophone supporters), MAC’s Marc Lanctôt, along with the show’s original curators, Kathleen Ritter and Tania Willard, and a number of participating artists led a tour of the exhibition. Many of the artists involved come (or are displaced) from communities not unlike Elsipogtog that remain subject to disenfranchisement, governmental disregard and daily human rights abuses. Here we all were, hermetically and hermeneutically sealed in the white cube, while snipers were pointing rifles at Mi’kmaq elders, protestors were being arrested for doing little more than drumming, dancing and singing, and mothers and fathers were attempting to shield their children from the onslaught of tear gas and other agents of violent control.

What the hell were we doing in a gallery, calmly but reverently discussing the power of contemporary art, when we could be out on the streets in outrage and uprising? Despite the seeming disjuncture between these actions they are, of course, related. An exhibition like Beat Nation – making seen and heard the cumulative appearance and sound of contemporary First Nations cultures for Native and non-Native audiences alike – has the strength and capacity, we believe, to crack open a wider conversation about the all-too-often unacknowledged contemporary concerns facing First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities.

This is, perhaps, of particular importance in the province of Québec, where Indigenous issues are so often overwritten and undermined by the continuing conflict between Canada’s two main colonial powers. We have to wonder how this exhibition will play out politically in Montreal, compared with Vancouver (the city in which it originated) or the other places it has visited. There is something of a political paradox in this province wherein language, land and cultural preservation are central to Québecois concerns, while also being of paramount importance to the pursuit of decolonization and the ongoing efforts of Indigenous artists and activists.

While debates rage throughout the province over the controversial Charter of Values (or, as we’re supposed to succinctly refer to it now, The Charter Affirming The Values Of Secularism And The Religious Neutrality Of The State, As Well As The Equality Of Men And Women, And The Framing Of Accommodation Requests), and the insistence that immigrants learn to assimilate in order to be accommodated, little acknowledgment is paid to the fact that this entire ideology is itself imposed and immigrant. It is, in fact, arguably insulting to the Indigenous inhabitants of this land who have, themselves, endured centuries of aggressive assimilation attempts by uninvited settlers.

With all of this in mind, the arrival of Beat Nation in Montreal is both timely and about time.

Bringing together 28 artists from across North America, Beat Nation explores the development of hip hop culture within Aboriginal communities and its influence on art making. The curators refer specifically to hip hop in the 80s and early 90s when it was more evidently conscious, political and social – about rebellion, protest, empowerment and mobilization for racially and economically marginalized communities. Through new mixes of language, syntax and vocabulary, the potential for a reconsolidation of cultural and political power was exercised. And the engagement with hip hop by the artists included in Beat Nation recharges the strength embodied by the originally counterculture genre.

As illustrated above, it is nearly impossible to sound cool when writing about hip hop in quasi-academic terms, especially when the hip hop in question has manifested itself in a quasi-academic art institution. So we will not rap the rest of this article. We mainly want to underscore the political import of the show.

From a curatorial standpoint, this is a rich and densely layered presentation of references and cultural overlaps that interweave issues of language preservation, land and territorial rights, and the ironic ridiculing and reversal of still-circulating stereotypes surrounding Aboriginal identity. The works are diverse, the layout expansive, and it would be impossible to cover everything, so in the spirit of sampling and remixing (and bad puns), here’s a brief rundown in no particular order:

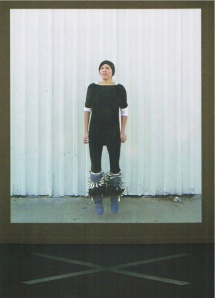

Anishnaabe artist Maria Hupfield’s video projection, Survival and Other Acts of Resistance (2012), depicts the artist jumping up and down in jingle boots on an endless loop, setting the bells in a steady rhythm. A large “X” on the floor in front of the projection invites the viewer to join in and jump in solidarity with her. A hop to the left is Hupfield’s Space Time Interface (2011): a shimmering silver wall comprised of emergency blankets. It similarly engages our bodies as it ruffles gently when we pass by, evoking any number of associations (including the fraught history of the blanket as a colonial implement of genocide, the insinuation of being lost in the wilderness and our dependence on synthetic materials for survival).

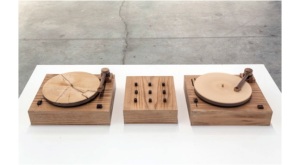

Sharing the space with Hupfield’s works, Sonny Assu of Weka’yi First Nation combines his series of 137 copper records (one for every year that the Indian Act has had legislative control over the lives of Indigenous people) and 67 painted elk hide drums (referencing the length of time that the potlatch ban was in effect) with a collection of records featuring the artist’s great grandfather recorded in 1967 by musicologist Ida Halpern. The combination of these objects articulates the contradictory program of cultural preservation and prohibition at the centre of the colonial project. Even more than this, however, it represents the resilience of those subjected to such policies and proscriptions. There is a similar sentiment to Jordan Bennett’s Turning Tables (2010), a wooden record player that quietly projects the artist’s own voice learning his native Mi’kmaq. The needle picks up a sort of static as it passes over knots and cracks in the grain of the wooden records, subtly echoing other artists’ allusions to preservation while widening our historical purview far beyond the colonial encounter.

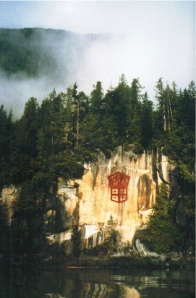

Issues around language are raised by countless works within the exhibition, including Métis/Cree artist Cheryl L’Hirondelle’s 2004 uronndnland (wapahta ôma iskonikan askiy) and Kwakwaka’wakw artist Marianne Nicolson’s Cliff Painting (1998). Both are photographic documents of performative works that draw links between land, language and identity through processes of making marks on the physical landscape. Working within vastly different contexts and referring respectively to displacement and territorial ancestry, the actions of both artists physically and symbolically lay claim to land.

Jackson2Bears’ video installation, Heritage Mythologies (2012), remixes footage from the government’s 2008 apology to residential school survivors, shot through in negative lens exposure, with archival images of protests and popular media. The visuals are set against a soundtrack, equally altered for effect, of iconic Canadian songs (witness the corpulent countenance of Rita McNeill belting out “our home and native –native –native—land”). With an overwhelming use of red – in the Canadian flag, in fire and blood – Heritage Mythologies obscures any easy interpretation of “the nation” or of national identity.

Kent Monkman’s Dance to Miss Chief (2010), is a polished-beyond-pastiche music video, in which the artist’s alter-ego Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, swivels and sashays to lusty beats and seduces Winnetou, Karl May’s fictitious “Indian” made famous in German Western films and represented by white actors in redface.

Tucked into a room just outside the main exhibition space, Swampy Cree filmmaker Kevin Lee Burton’s 2008 video installation Nikamowin (Song) arguably encompasses all of Beat Nation’s most dominant themes. Filmed from the window of a car, the video registers the changing landscape from a reserve in God’s Lake Narrows to the streets of downtown Vancouver. Acoustic elements of the Cree language are re-mixed and recalibrated to produce the beat-driven soundtrack. The work provides a rhythmic and politically charged comment on the preservation and evolution of language and the fluidity and forward motion of “tradition.” Whether you see Nikamowin first or last, and whether you catch its beginning, middle or end, it is always in motion and always in flux.

For the curators’ repeated emphasis that the show is loud, there are many cases in which it could be much louder. The effect of Nicholas Galanin’s two-part video work, for example, in which a contemporary dancer moves rhythmically to traditional Tlingit drums and vocals and a Tlingit dancer, dressed in full regalia, moves to an electronic soundtrack, is easily diminished as a result of its low volume. One might even wonder where the low hum of the music is actually coming from. It’s not coming from Duane Linklater’s red neon eagle, Tautology, on the nearby wall (we checked).

In other cases it comes down to a matter of placement. Bennett’s Turning Tables, for example, is a rich and emotive installation that is completely overwhelmed by the booming acoustics of Bear Witness’s equally fantastic video installation Assimilate This! in the room next door. This arrangement, however, could be understood as part of the exhibition’s conceptual strength, as it necessitates some strained and careful listening to Bennett’s recordings while bent as close to the work as the museum guards will tolerate. Bennett’s grainy voice seems already far away, as though its continued presence is not guaranteed but dependent on attention and care.

Moreover, while a show like Beat Nation, which combines so many cultures under the broad heading of “Aboriginal,” easily opens itself to criticism for essentializing Indigenous identity, the raucous atmosphere of the show metonymically reinforces the fact that there is much variation among the differing voices and subjectivities included, and arguably addresses the all-too-important fact that there is no single “Aboriginal” culture, but diverse and numerous Native nations. Significantly, the choice of artists included in the exhibition was not limited to the arbitrary political or geographical frontiers that were drawn across the landscape by colonizing powers—an exercise and exertion of colonial control and the deterritorialization of First Nations in the first place – but organized primarily around shared themes, methods and media.

The famous slogan of the 1970s feminist movement reminds us that the personal is political. That is, the efforts and actions of one group’s quest for self-determination is the business of everyone. Everyone on this land mass has a responsibility to recognize how contested is the land below our feet. When our own Prime Minister can claim that we have “no history of colonialism,” its pretty clear that we’re in need of better education in this country… and a better Prime Minister.

The characteristically light pedagogical hand of the MAC has left much history and background information off the walls of Beat Nation. While that is something we often appreciate, in this case, might the lack of context diminish the political impact of the exhibition?

One crucial and immediately practicable effect of the exhibition is its rendering visible the paradoxes and persistence of colonial logic in our everyday surroundings. One afternoon, outside the museum, a young woman wearing one of those redesigned HBC blanket coats could be seen sitting beneath a giant poster of Skeena Reece costumed for her performance Raven on the Colonial Fleet. The juxtaposition between the ironic and strategic mixture of cultural signifiers and their deconstruction in Reece’s performance wear contrasted dramatically with the unironic and unreflexive donning of a symbol so replete with disconcerting colonial connotations that the pairing of these two figures almost smacked of parody.

Up the street in the HBC itself, a small maquette at the cash register, colourfully decorated with the Canadian flag and the HBC blanket stripes, chirps the tagline “We were made for this.” WE were made for WHAT? It’s almost laughable, but hardly funny. It’s absurdity becoming obscene: the HBC blanket is a potent symbol of the genocidal actions taken against Aboriginal people in this country, but is also an emblem of Canadian national identity, and all of this is wrapped up in the same cheerful commodity that continues to be marketed and sold. In fact, it is this kind of double signification that informs the strategy behind so many of the works included in Beat Nation: the re-staging of highly loaded cultural clips and images to reveal their utter ridiculousness as appears in the work of Kent Monkman, Jackson2Bears, Bear Witness and others.

What is most disturbing is how unreflexively pervasive and persistent the colonial mentality remains in Canada and often in the service of consumerism and/or tourism. Between the embarrassing Inukt fiasco at the Musée des Beaux Arts and how narrow the fears are that drive the Charter of Values, this has been all too obvious in Montreal as of late. Most insidiously, the battles waged over the French and English languages, territorial claims and cultures continue to blind Canadians to the fact that First Nations were here, speaking their own languages and occupying their own land long before the field where one of the big “historic” events took place was even renamed the Plains of Abraham. This exhibition is an important one and should be ideally visited by all Canadians. It makes visible and audible the contemporary and continuing presence, resilience, resistance and vitality of First Nations, Inuit and Métis cultures. But it also makes evident the fact that we still have a long way to go.

Reilley Bishop-Stall and Natalie Zayne Bussey

© Passenger Art, 2013

Beautiful and sensitive writing, thank you so much Passenger Art! I tried to see this in Toronto last year but didn’t make it, so I am happy to see it here.

It is hard for me to reconcile the issues presented in the beginning of this article. The complete and ongoing disregard for the human rights commission on Indigenous issues is so unbelievable and painful to witness, especially after so many attempts at resistance. And at the same time, as I write, I remember filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin talk of hope at a screening of her documentary THE PEOPLE OF THE KATTAWAPISKAK RIVER at Cinema politica. She said that in her lifetime, she has already seen a huge changes in the treatment of Indigenous people, which is hopeful on one hand and completely depressing on another, but she intended hope, so that is what I will have!

I suppose change happens on many levels, and while there seems to be a disturbing dissonance between settler spectacles such as the museum exhibition of Indigenous art, and Canada’s ongoing abuses I guess, the “hope” is that these kinds of exhibitions will contribute to some kind of shift, as you infer with this article. But, I suppose that leads me to wonder, is hope itself action? What happens after the show closes, does the pleasure we experienced from witnessing the eloquence of an others struggle mobilize those who do not feel the effects of that struggle? Can we invigorate courage in those standing against the violence of our state? Can our hope subtly seep into the mind of the officers holding weapons against families on behalf of corporate interests. It would be nice. What do you think?

Sorry for the rant! I suppose in finishing, it would be my wish that this kind of visibility for Indigenous people didn’t only happen during a few months in a gallery, but was continuous throughout our cities, reminding us that in fact, we are on native land!

Thank you for this!

Thanks for your thoughtful and articulate comments Missnesbitt. With such incredible gaps between progressive movements and “official” and corporate actions, it’s hard to assess with much confidence where we’re headed and how fast.

A lot of people we spoke to about the show—intelligent, educated and culturally conscious people in the main—felt they didn’t know enough about colonial history and Aboriginal cultures and concerns to fully “get” the works in the exhibition. It’s a tricky issue, one we grapple with too. It wasn’t necessarily meant to be a pedagogical show, but more a presentation of contemporary culture (various First Nations, hip hop, street, etc.) via strong works of art. We like to think that the lack of didacticism on the exhibition walls is positive because it compels viewers to think and wonder, and hopefully do our own work in excavating and rebuilding the contexts from which these works derive.

If we don’t contend with the past and acknowledge the retention of colonial structures in the present, we cannot possible move forward as a society. This needs to be part of every school’s curriculum. It needs to part of everyone’s daily consciousness. It must be nauseatingly obvious to those who have been part of the struggle for Indigenous land rights and preserving the environment, but Beat Nation helps drive home the fact that the future of us on this land is dependent on learning about the past and acting in the present. This country is out of whack and needs to do some major work on itself, like national therapy. It seems that by attending to this, by keeping the past open for reconsideration and staying open to who is trying to be heard in the present, we can also make better decisions regarding immigration, the environment and our foreign policy as well.

Maybe hope can be action, like awareness and acknowledgment. A museum exhibition is definitely not enough and yes it’s temporary, but what it does do is draw attention to the struggles that are consistently being fought and the amazing work being done by activists, artists and scholars on individual and community levels. We have hope because of these kinds of conversations. The more discussions like this that happen, the less likely that stupid remarks like Mr. Harper’s will be heard, and—hopefully again—will eventually not be said in the first place.

Thanks again for getting in touch!

I am only just seeing this lovely reply now! Thank you! Your words are well spoken, and, as I am growing in my own understanding about the place of exhibitions to address colonial issues, I agree with you! It is extremely important to show contemporary work by Indigenous people as one part of a complex web of needs. Thanks again!

Reblogged this on miss nesbitt and commented:

Lovely review by the Lovely Passenger Art

There’s an open pane at Concordia this Saturday on ‘Supporting Indigenous Sovereignty and Self-Determination’,for those of you that are interested. https://www.facebook.com/events/620784381317428/?ref_dashboard_filter=upcoming

Excellent reporting, commentary and gallery review, on probably the most important issue in this country today. I was so impressed by James Anaya’s report and so depressed by the government response. But there will be progress thanks to voices like Passenger Art. Well done!

Thank you! It certainly does feel like one step forward two steps back with this government (and, unfortunately, just about every one that preceded it). In fact, as a good friend of Passenger remarked, this was precisely the case with the concurrent opening of Beat Nation and the launch of the Inukt line at the Musée des Beaux Arts. Passenger friend Jason Gladue, both inspired and buoyed by the work his peers are producing and so deflated by the bullshit lining the shelves of the beaux-arts boutique said it well: “It seems like it’s always going to be like this. Every time we gain a little ground, colonial society finds a way to put us back in our place.” Let’s turn things around so that instead it is every moment of racism, ignorance and inequality that is counteracted by positive action and change.

Pingback: Beat Nation Resources | Curatorial Theory and Practice

I saw this show in Vancouver and am grateful to revisit it through your thoughtful and passionate writing. Living on Haida Gwaii it is shameful to me how so much of Canada is totally ignorant to the history of Aboriginal people as well as the resilience and evolution of art forms coming from the various nations. The story about the Inukt is so embarrassing. I’m curious to know what happened with that! Did they remove that stuff from the gift shop? It’s so offensive!

Hi Alicia,

Thank you for your comment. The Inukt line was ultimately removed from the museum’s boutique, due in large part to outcries from the artists and curators of Beat Nation as well as much of the concerned public. Even then, however, in all public statements the designer has remained ignorant of or unwilling to accept the offensiveness of her project. While the boutique’s manager made a public apology, her stance was simply that the museum’s gift shop was likely not the right venue for sale of the fashion line, effectively sidestepping the issue that it shouldn’t have been produced or be sold anywhere at all.

Pingback: First Nations, Metis, Inuit Stereotypes in our Media | Big Ideas in Education

This is really interesting, You are an excessively skilled blogger.

I’ve joined your feed and look forward to looking for more of your magnificent post.

Also, I have shared your website in my social networks

Thank you very much! We appreciate it.